By Ndidi Chidomere (Senior Lecturer in Pre-qualifying Health Care)

Aim of this ‘ideas Factory’: To share my experience with colleagues, Educators, Researchers, leaders and students on a completed apprenticeship project; reflectively highlighting some of the limitations, shortfalls and successes for learning purposes. I hope that this brief recount will empower the less confident researchers wishing to embark on similar projects.

Project title: ‘Exploring the ‘T Trust’ nursing apprenticeship programme: The lived experiences of the pilot cohort’.

Project aims were to explore the feelings and views of seven new Health Care (Nursing) Assistant (HCAs) Recruits after a year into their apprenticeship programme in order to; identify evidence–based challenges and successes of the recruitment and support processes offered towards their professional development.

Though done primarily as work-based while I worked (as Educational Facilitator) with a London National Health Service (NHS) Trust to boost my leadership skills and those of the apprentices’ mentors; it was also as a part of an academic progressing assessment towards my Masters of Arts (MA) qualification.

Participants: Seven available and consenting Nursing Assistant apprentices on completion of a year pilot programme.

The Researcher: Myself as the MA student (a Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) registered Nurse Teacher and a General Nurse) working with NHS as Educational Facilitator as well as the Leader for Bands 1 to 4 staff.

Brief background information

The objective of the apprenticeship programme was to recruit, clinically and academically develop young local adults who do not meet all the University criteria for University nursing admissions but are compassionate enough to render care within the NHS. These candidates subsequently progress as student nurses. Therefore, the employing local NHS Trusts engage and support the Apprentices clinically as well as sponsor their academic progression in partnership with other organisations. The ‘T Trust’ apprenticeship was in partnership with Health Education England (HEE), Local Job Centres Plus and a London based University as the Higher Educational Institute providing the academic support.

One of the underpinning frameworks was the Health Education England’s (HEE, 2014) ‘National Talent for Care Programme Partnership Frame Work’ in partnership with a few other organisations and establishments such as National Skills Academy for Health, Skills for Health, Social Partnership Forum, Trade Unions and the NHS Employers (to which I belonged). This was in line with the decision by the Department of Health (2013) to improve care in England; widen the recruitment pathways of nurses’ training by investing in the development of HCAs following the events of Mid -Staffordshire Hospital and the Lord Francis final Report (2013). Some individuals hoped that engaging local youths might indirectly reduce crime rates within the engaging communities.

Understandably, recruitment and training of student nurses is a rigorous process (NMC, 2018) underpinned by safety. Additionally, every NHS nurse expectantly is to demonstrate ‘6Cs’ (care, compassion, communication, commitment, competence & courage as emphasised by Professor Jane Cummings, the then Chief Nursing Officer for England (2012). However, a large number of candidates who demonstrate compassion are short of all University entry requirements.

Hence, ‘T Trust’ HCA apprenticeship is one of the new routes to identify and recruit into the NHS those compassionate and caring candidates who may not necessarily immediately possess the full academic qualifications for the University direct entry nursing admissions. It involved supervised clinical and academic in-house and external support for the Apprentices, their mentors and their Educational Facilitators following rigours apprenticeship recruitment exercises. Programmes included varied learning workshops by the partner University and the HEE with Apprentices’ final assessments and ‘signing off’ activities by the ‘Assessors’. A few registered nurses volunteered and attended the specially organised ‘Assessors’ workshops for mentoring and also assessing the Apprentices’ workbooks to become ‘Pilot Assessors’. However, other nurses and senior HCAs could supervise and support the apprentices.

Methodologies and approaches used for the Research

A Census approach; qualitative research-using semi structured interviewing questionnaires. This ensured participants’ freewill participation; offering flexibility to explore the participants’ answers. Initial ethical clearance from the University and the NHS Trust as well as gaining permission from the candidates and their managers were completed. There were lots of planning, meetings and discussions with the candidates and reassurance to remain anonymous and brain- storming for research questions and literature reviews. I waited to secure conducive times and adequate interviewing rooms for each candidate during their working hours without necessarily disrupting the flow of care or compromising safety; that required a lot patience.

Voice recording (and simultaneously typing into a secured laptop) of the interviews provided accuracy.

Coding, storing and transcribing protected the candidates’ identities in line with the Ethical Committee’s policies (National Research Institute, 2014) and the NMC (2018) Codes of Conducts. Data were decoded, findings analysed and compared against results from literature reviews and seminar discussions on similar globally and nationally previously completed projects and outcomes were insignificantly different.

Results: Demographically, there was no differences in the participants’ experiences. However, the different levels of support and information provided to Apprentices within different individual clinical units might have shaped their learning and experiences.

The study has addressed the research question (what was the lived experiences of the ‘T Trust’ (pilot) nursing Apprenticeship) and achieved the project aims; participants completing the apprenticeship programme have demonstrated 6Cs as trainees and acquired more qualifications academically.

All Apprentices recounted initial mixed feelings of joy and uncertainties (on recruitment) but later experienced worries, stress, tensions, anxieties, fears, uncertainties, sense of loss, confusions and rejections at different degrees and stages individually and as groups (on resumption and towards mid-point).

However, the great transformation of the Apprentices’ social, academic and clinical status was reflective in their recounted positive feelings at completion as well as visible confidence displayed clinically. The levels of Apprentices’ satisfaction and feelings were unascertained quantitatively with any reorganised scales. However, other multiple evidences were deployed resulting in all participants describing increased feelings of joy, fulfilment, success, acceptance, achievements, belonging, importance, usefulness, assertiveness, accomplishments, inclusiveness and professional confidence that emerged following their permanent employment by the NHS Trust as well as agreed plans to sponsor them as student nurses.

I as the researcher experienced almost same transformations as the participants both academically and psychologically having worked alongside all; I passed the MA assessment with noticeable leap in leadership, communication and negotiation skills as well as confidence (resulting in various Non-NHS job offers).

Other findings that emerged were around the short falls and challenges during the period. Thematically, the highest scorings centred on communications and others briefly appear below.

Challenges

Assessment, support and training process: Three quarter of the participants felt that some recruitment assessments by the Trust were similar to those already done with Job Centres Plus; hence repetitive and stressful.

Planning and organising the support workshops for the mentors was challenging due to limited resources, work politics and some unexplained issues. Some mentors could not timely attend or complete the ‘Assessors’ support workshops’; hence not well equipped with the mentoring skills required for the apprentices’ support. In fact, some denied all knowledge of the programme and saw the Apprentices as extra burdens on the overstretched capacities. Unfortunately, being a pilot, only a few Education team members had the experience and or proper training required to immediately support the Apprentices as well as their mentors (‘Assessors’).

Communication: Disseminating information was quite daunting; the Education Team where I belonged communicated mostly with the Directors of the Nursing (DoNs) and a few senior clinical nurse managers without necessarily directly involving the junior staff. There were wrong assumptions that decisions and circulating of information were for the ‘DONs but only a limited amount actually got to those ‘on the floor’ who were to work directly with the apprentices. Effective communication sometimes lacked among the Education Team because staff worked across various sites and locations without official mobile devices for effective communications. Besides, the office computers were not always easily available to all staff while visiting other sites as ‘hot desks’.

Uncertainties: There were periods of uncertainties, confusions and even fears expressed by the candidates and sometimes by me. A few candidates experienced some role uncertainties;many people (including employed staff) did not realise that the apprentices had no pre recruitment nursing experience and so confused them with the employed (experienced) HCAs or even the ‘proper student nurses’. Lack of specified apprenticeship uniform made it more confusing; ‘T Trust’ Apprentices wore same uniform as the employed, experienced Nursing Assistants. This created amusing dilemmas on the wards. Some of the existing HCAs wondered on whether to accept the apprentices as ‘new special student nurses’ or as fellow employed HCAs or ‘young colleagues’ or even ‘as threats’. Therefore, a few did not initially accept nor co-operate with the Apprentices and this affected me indirectly as their leader (details in my main project).

Literature reviews: Retrieving enough National materials (within the ten years bracket) on primary research around nursing apprenticeship was time consuming because nursing apprenticeship was relatively new in the England; not a lot were available globally either.

Writing and transcribing the scripts: Interviews anonymised, coded, and electronically recorded with mobile device provided by a special department within the University. Keeping eye contacts while asking questions as well as typing the responses simultaneously was quite challenging for me as a novice Researcher.

Decoding and transcribing the information was sometimes confusing and took longer than anticipated.

Time/ sponsorship: As a novice, I underestimated some timings for activities. For instance, time to access and appraise evidence from literature and other sources appeared to go too quickly and I could not timely get information on how to ask for research funding nor sponsorship application for qualified transcribers. Drafting the weekly activities for the apprentices and Assessors’ monthly workshop programmes within the Trust as well as liaising with University faculty staff for the apprentices’ academic work (while I worked full time) was sometimes mentally and physically draining.

Success: contributing factors

- Special support from University and my Head of Education (the NHS Trust);

- My dedication, passion, commitment to learn and support learning;

- Positive attitudes such as resilience, humility, openness;

- Utilising feedback; and collaboration;

- Working with professional boundaries and seeking help;

- Previous experience as a nurse and teacher.

Tips

People undertaking and leading projects have to avoid assumptions and claim ownership in order to facilitate and disseminate the specific project’s agenda and spread information across all levels but supported by managers.

Leaders need ‘enough time’ to conduct successful projects and the less experienced researchers possibly be guided and adequately supervised or supported. Lack of sponsorships and supports of all kinds may negatively affect quality of work and the comparative findings.

Having contingency plans such as alternative support plans for students (should a mentor move, retire or suddenly becomes unavailable due to ill health) should be put in place even prior to accepting apprentices’ on placements. It is of immerse value to save one’s work in different locations due to sudden data loss which are avoidable

Anticipating and planning for financial gaps between the acceptance period and that of first payment of salaries may reduce anxieties and mistrust.

Collaborating with ward staff early enough but in an open and two way process as well as other professional and multidisciplinary team members at work (and externally when necessary) yields better results especially, by seeking experts’ opinions as well as appreciating the activities of the clinical support technicians.

All staff and especially project Leads should emulate good professional attitudes such as politeness, humility and respect towards all as these in turn attract compassion, kindness and feeling valued from others who could offer help. This also reduces power dynamisms and eases tensions; hence, smoothens and quickens one’s project process.

Remaining honest to oneself is paramount. Projects are challenging and can become stressful and draining, so embark on project only if there is great passion for that in order to remain positive and committed until completion. In any case, asking questions, discussions and help with experts early may reduce assumptions, fears, errors, and failures.

Attending and valuing professional training in the form of workshops, seminars, webinars and reflective discussions and generously sharing one’s skills and experiences boosts confidence and enhances competency. Mistakes only give one another chance to improve.

Lessons

However, communication among Nurses still appears to be a major issue as was the case here. There may be some urgent need to share information across Universities and with those NHS Institutes engaging Apprentices on Apprenticeship, roles of Apprentices as well as the best supportive mechanisms. Some Apprentices may need greater support than we currently offer or even believe. Leading the apprenticeship project has highlighted some areas for attention; some under staffed placement Units may lose focus on the actual purpose and roles of this group of learners and so may not adequately provide the needed clinical support. Utilising Apprentices as fully employed staff can easily occur because of the notion that ‘they are paid’.

This is opposed to student nurses’ positions as unpaid and supernumerary. In fact, the direct entry– route students appear to have more freedom and support because they ‘pay’ tuition fees. Therefore, Apprentices would benefit from clearer contracts, role identifications, setting of professional boundaries as learners while on placement and not undertaking their part of ‘employed roles’. There may be need to have national distinctive uniforms that distinguish Apprentices from the existing paid HCAs (or support workers) and student nurses when on placements as learners.

In addition, more awareness on the objectives of apprenticeship needs greater publicity but with less focus on the politics and ‘cutting costs’ as these may hinder recruitment and retention. Mentors (supervisors and Assessors) may need more support than the NHS management currently offer. The clinical areas are facing many staffing challenges and struggling to keep up with the boost in information technology while ensuring safety. Ensuring this within a calmer and supportive environment may reduce tensions, fears and mistakes. Hence, openness and honesty among all nursing levels on how to support learners is very important if we are to reduce the current nursing attrition rate.

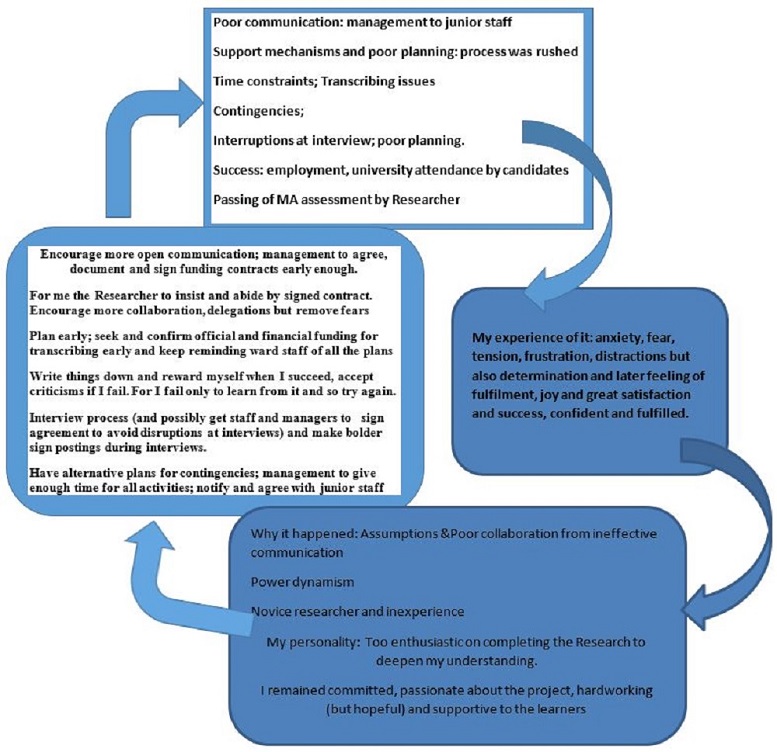

Shortfalls/ limitations& Success: what happened?

My reflection using Schon’s (1991) model

If you wish to submit a proposal for a future Ideas Factory post please submit using this form.

Useful Sources

Chidomere N H (2015) Unpublished data The ‘T Trust’ Apprenticeship programme: what were the experiences of the pilot cohort’ (Academic and NHS Trust work, awaiting publication); available on request for teaching purposes only.

Department of Health (2013) HCA competency framework –a consistent approach to learning and the delivery of quality care; presented at Nursing Event Chelsea, London 16 October 2014.

England Chief Nursing Officer (Jane Cummings, 2012), the 6Cs: South Manchester Nurses annual Conference December 12th, 2012 on line at http://www.england.nhs.uk/nursingvision/actions/ and http://www.mkupdate.co.uk/conferences/developing_the_role_of_healthcare_support_workers. Last accessed 25th May 2019.

Francis report (2013) The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry final report: Executive Summary. [Available on line] http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report Last accessed 20th October 2019.

Health Education England (2012, updated, 2015). Shape of Caring Review: High quality Education and Training for Nursing and Care Assistants. [Available on line] at https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/shape-caring-review (Last accessed, 20th May, 2019)

Health Education England (2014). Research and Innovation Strategy: Developing a Flexible Workforce that Embraces Research and Innovation. Available at: http://hee.nhs.uk/ wp-content/blogs.dir/321/files/2014/05/RI-Strategy-Web.p [accessed 23rd May, 2015]

Health Education England Strategic Frame work (2014). Health Education England Strategic Frame work: Framework 15 Health Education England Strategic Framework 2014 -2029 (knowledge, Care and Compassion; pp 97-100 ( Updated February 2017) on line at https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HEE%20strategic%20framework%202017_1.pdf. (Last accessed on 6th June 2019).

https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Duty-of-Candour-2016-CQC-joint-branded.pdf. (Accessed 20th May, 2019)

National Research Institute (2014) Conduct of Research guidelines National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). [Available on line] at http://www.nihr.ac.uk/research/22 July 2014-policy and standards. (Last accessed 6th May 2019).

Nursing & Midwifery Council UK (NMC, 2018) Becoming a nurse: how to become a nurse or Midwife or Nurse Associate in the UK [on line] at https://www.nmc.org.uk/education/becoming-a-nurse-midwife-nursing-associate/becoming-a-nurse/ (accessed 20th May, 2019).

Nursing & Midwifery Council. (2018).The code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council.

Schön, D. A. (1991). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco.

Appreciations: My heart filled gratitude to Melanie Pope (Associate Professor, UOD) and Richard Harris (Dep. Admin Officer, UoD) for their patience, time and commitment in supporting me to undertake this Ideas Factory activity.